(This is actually an old article which was originally published on the India Law and Technology Blog, where once upon a time I was a regular guest blogger. Unfortunately, sometime back all of them got wiped out. I often get messages about those posts, but sadly many of them were typed directly on the wordpress platform. Hence, no copy and as a consequence, permanently lost. Fortunately, while rummaging for something else, I chanced upon one of my earlier posts from the days when I still preferred to type a word draft first.)

At the very outset, I must confess, I have never been an absolute supporter of network neutrality and still am not. Another writer on this Blog has written before that he feels that the internet is inherently discriminatory, and I am inclined to agree with him. The writer of that post has summarized the reasons why the subject has become such a debatable issue among the learned, yet one can find that the subject has failed to convincingly grip the imagination and attention of the general pubic. And the various research papers and articles written and published in various journals of repute by the proponents of network neutrality are in the writers personal opinion, often too complex and long to enlighten and help an average reader to engage in an active debate on the topic. (After all, few individuals, except for law students or lawyers, will take the pains to read a seventy seven page article in the Harvard Journal of Law and Technology!!)

Notwithstanding what has been written above, THE MASTER SWITCH by Tim Wu is a welcome change to such articles. It is everything that should be asked of a book on a policy issue: Concise, simple, interesting so as to be able to grasp the attention of the reader, and most importantly, synchronized with itself, i.e., all the chapters within it. It also helps to better justify his stand as a proponent of network neutrality by using the “destruction of innovation” argument, which he failed to adequately explain in his papers and which has often been made into the weak link in the armour to be exploited by the those not in favour of network neutrality.

To summarise, he has used the Schumpetarian cycle of “destructive creation” to try and justify why there is a need to enact a Network Neutrality Legislation. He shows through historical examples how each new innovative medium of communication, from the Telegraph to the Television, has over time, though born as an innovative new and “free” medium to communicate, has slowly been centralized and been absorbed to be manipulated and controlled by the few large corporations who have eventually come to dominate the American industry and even Government policy. He then talks about how the Internet is a medium far more revolutionary then any of its communication predecessors and hence, any centralization of this medium shall, in fact result, in an unacceptable loss of freedom of expression.

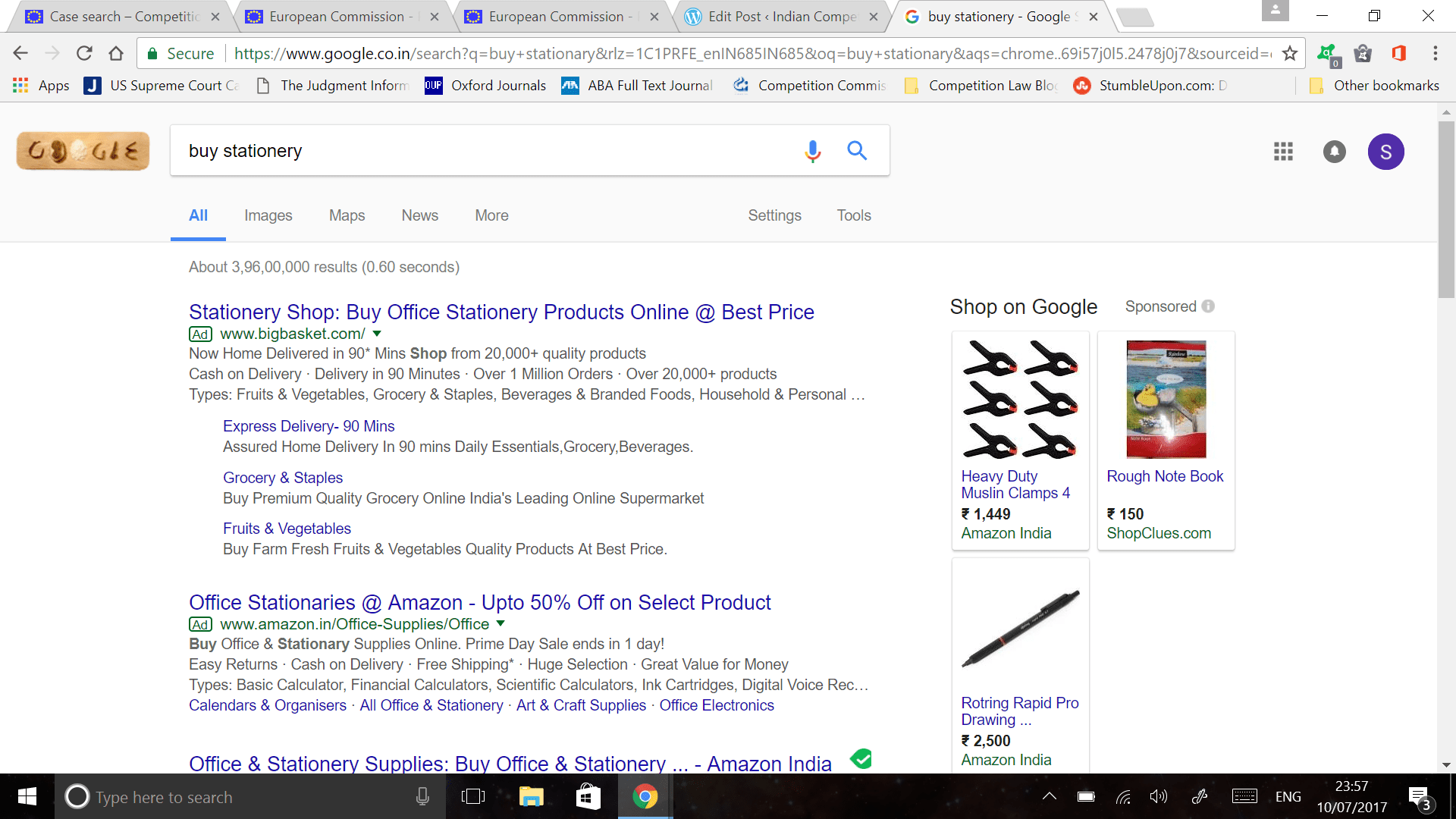

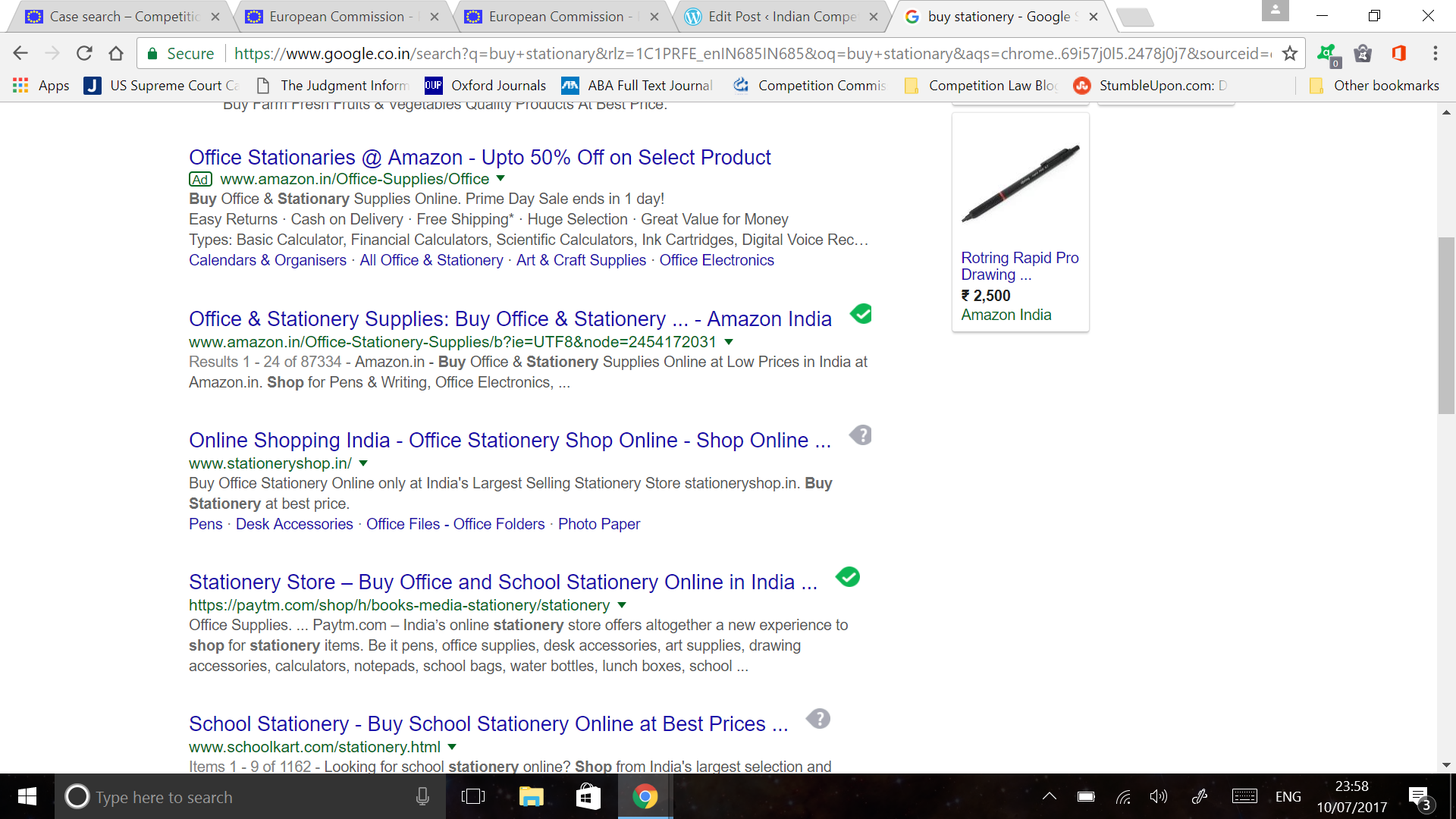

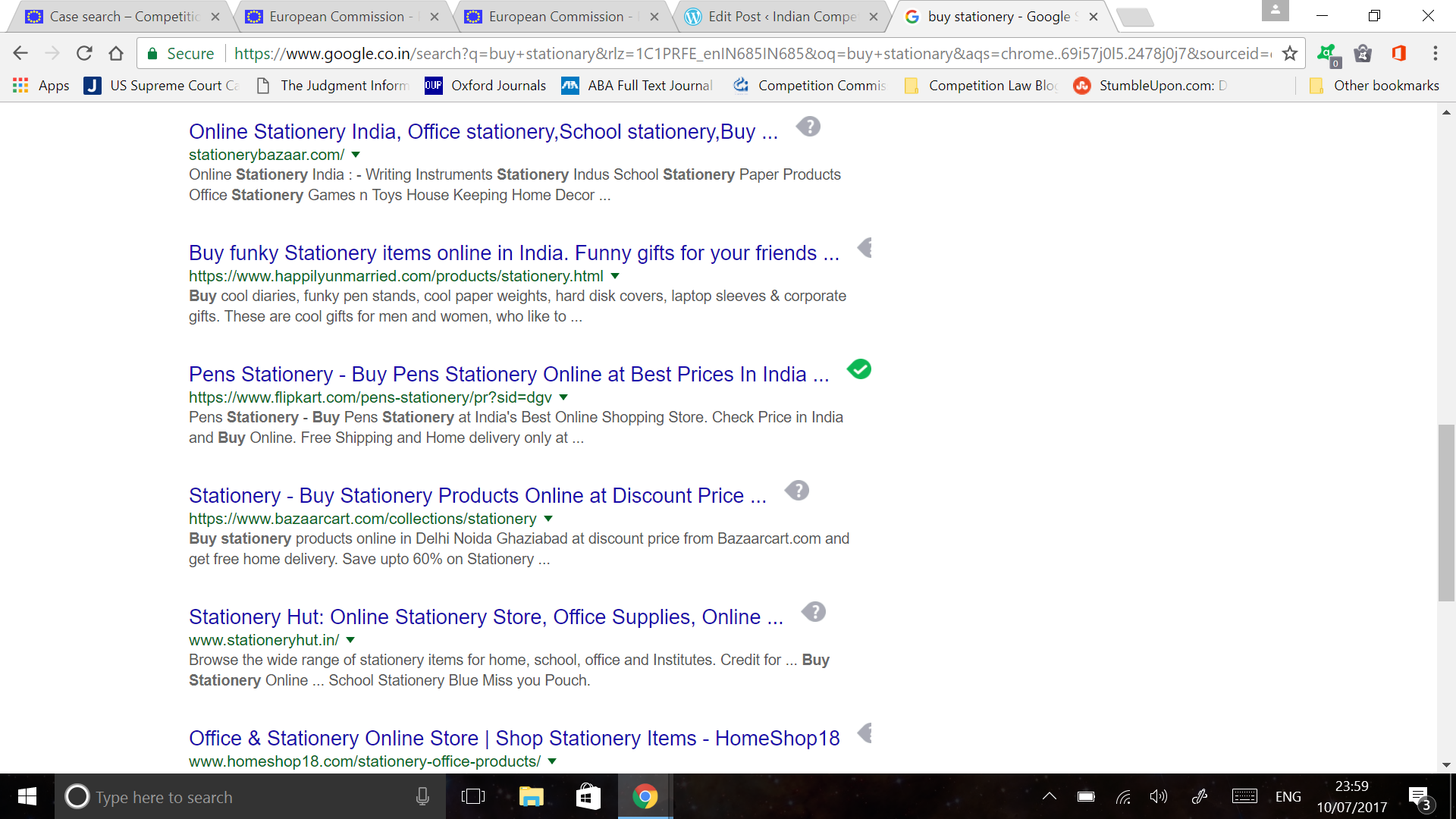

After reading the book, one begins to understand that the reason a Network Neutrality Legislation needs to be enacted is not with the de jure intention of necessarily keeping the internet neutral, but with the de facto intention of actually controlling corporations from gaining too much control over the medium. A question which arises at this point is “why do we need a specific legislation? Why is the FTC (or, in India’s case, the CCI) not enough to control such an abuse of dominance, should it ever arise?” Wu answers this question, by again, citing historical examples on how these corporations have, through their clout, managed to subvert or walk around such Anti – Trust procedures through effective and efficient lobbying in the U.S. Congress. Despite its lack of effectiveness though, it is interesting to see how Anti – Trust law can act as an effective tool to against network discrimination.

If a complaint has to be raised against the book, it would be that for some reason it lacks any mention whatsoever of Facebook, which is quite surprising considering the status and clout which the site has achieved to influence individual opinion in our times. However, after reading, I must confess, I am far more convinced for the need for specific legislation on network neutrality than I was before.

As a post script, for all those interested in understanding the issue of network neutrality in simple language devoid of most technicalities, I recommend the following essay by Edward W. Felten:

http://dreadedmonkeygod.net/home/attachments/neutrality.pdf

In a rather interesting/unforeseeable turn of events, the Ld. single judge of the Hon’ble Delhi High Court (‘DHC’) has come down heavily on a Petitioner seeking relief against a Section 26(1) Order passed by the Competition Commission of India (‘CCI’).

In a rather interesting/unforeseeable turn of events, the Ld. single judge of the Hon’ble Delhi High Court (‘DHC’) has come down heavily on a Petitioner seeking relief against a Section 26(1) Order passed by the Competition Commission of India (‘CCI’).