There are certain cases in any area of jurisprudence in law, including competition law, which tend to make an individual mark of their own. This may be simply due to the parties involved, or because the cases involve seminal questions in law which would help clarify the legislation involved for future use, or because the ramifications (not necessarily negative) of the Final Order go beyond just the law involved, and into the arena of a change in the very economics or social structure of the system the case may question.

In my personal opinion, Fast Track Call Cab Pvt. Ltd. and Anr. v. ANI Technologies Pvt. Ltd., Case No. 6 and 74 of 2015 falls into this category and for all the reasons stated above.

My criticism of past Orders of the Commission through this Blog is well known, but this time, I must bring on record my appreciation. The Final Order is by no means perfect or maybe even completely legally sound in all aspects, but it does display not only the growing maturity of competition jurisprudence by the Commission, but also at least an attempt by the D.G. to not be content with a superficial investigation of relevant market dynamics.

Both Ola and Uber have already suffered enough regulatory troubles regards surge pricing and driver registration from various transport departments across the country, and though Ola has won this round, there will most probably be an Appeal. But the biggest fallout for Ola (and even Uber), which in my personal opinions has made it a pyrrhic victory, is that the D.G. and the Commission have extensively written about the below cost pricing strategies adopted by both companies. In fact, the D.G. has gone so far as to note that the significant market share of Ola or Uber has nothing to do with technological innovation but is rather the pure consequent of below cost pricing. Whether the companies like it or not, it is probable that both Ola and Uber will be prodded to bring down the revenue drain, not just by investors but also by competitors and various state departments as economically, a market providing services below cost can under no circumstances be considered an economically sound market, and creates potential avenues for future investigations by the Commission.

COLLECTIVE DOMINANCE BACK IN THE LIMELIGHT

An alternative argument which was raised by the Informants while objecting to the D.G. Report was that there is a possibility of two entities exercising dominance at the same time. The Informants claimed that the analysis of the D.G. pointed towards the presence of more than one dominant player in the relevant market. Furthermore, they submitted that the D.G. in its report had admitted the growth of both Ola and Uber was not the result of any technological innovation or efficiency but the result of a practice to charge substantially below the average variable cost. The Informants also quoted the observations of the Canadian Competition Tribunal in the Visa Mastercard Case, which noted that both MasterCard and Visa can individually possess market power in the relevant market. It was thus submitted that a conclusion of simultaneous dominance of Ola and Uber was not incompatible with the provisions of the Competition Act, 2002.

I have already on a number of occasions discussed Collective Dominance (See here, here and here) and how it is not presently recognised under the Act. The Commission’s reasoning is similar to what we have already propagated here and I have nothing new to add in this area.

However, for the fun of it, let us hypothetically presume that Collective Dominance was recognised under the Competition Act. Could Ola and Uber have been held liable for abuse of dominant conduct ?? I would submit the answer would still be a no.

Firstly, since the Uber investigation has been stayed by the Supreme Court, no finding or penalty could be imposed upon Uber. But beyond that, secondly and more importantly, is that Ola and Uber would never be able to breach the threshold for Collective Dominance under Competition Law, and to understand why one needs to look into the case of U.S.A. v. VISA Et al., 344 F.3d 229 (United States Court of Appeals, second Circuit.). Similar issues were raised against VISA and Mastercard. To summarise, the United States Department of Justice brought enforcement action against the two payment card networks and licensor of one payment card brand, alleging that governance duality between networks and networks’ exclusivity rules were agreements in restraint of trade in violation of Sherman Antitrust Act. Challenging the organizational structure of two of the nation’s four major payment card systems, the complaint charged that MasterCard and Visa U.S.A., which are organized as joint ventures owned by their member banking institutions,conspired to restrain trade in two ways: (1) By enacting rules permitting a member-owner of one to function as a director of the other (an arrangement the government described as “dual governance”) (Count I); and (2) by enacting and enforcing “exclusionary rules,” which prohibit their member banks from issuing American Express (“Amex”) or Discover cards (Count II).

The Court held that Visa U.S.A. and MasterCard violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by enforcing their respective versions of the exclusionary rule, barring their member banks from issuing Amex or Discover cards. The Court further held that Visa International, which owns the Visa brand, licenses it to Visa U.S.A., and exercises certain governance powers over Visa U.S.A., was liable for participating in Visa U.S.A.’s violation. Factually, it is important to note that a member of either the Visa U.S.A. or MasterCard network could also be a member of the other network. Thus a bank that was a member of Visa U.S.A.’s network and issued Visa cards could also be a member of the MasterCard network and issue MasterCard cards. On the other hand, both MasterCard and Visa U.S.A. had promulgated rules that prohibited their members from issuing American Express or Discover cards. Evidence was also cited that atleast three major U.S. issuer banks would have contracted with American Express to issue Amex cards in the United States but for the exclusionary rules.

In other words, in Visa Mastercard, there was active collusion between the two entities to limit market access to the other two competitors, whereas in the case of Ola and Uber, it is anything but !! Both companies are constantly at each other’s throats on pricing and volume of rides in the country. We are starting to see a cut back on the below cost pricing strategy, but only a continual market watch on the sector will help to gather enough data to understand the consequent effects, and it is too early to take a firm decision as of today. Since Ola and Uber have together effectively turned the market as one heavily based on network effects, strong competition and constant change in market share might be the norm between the two for some time to come.

POST SCRIPT: UBER IN INDIA

The Uber legal team would have been on their tenterhooks till this Order came out, and will be studying it closely (the investigation against Uber has been stayed due to questions of law regarding the powers of the erstwhile Competition Appellate Tribunal (COMPAT) and the matter is presently pending in the Supreme Court). The relevant market would obviously include Uber, and the D.G./Commission made a number of observations regarding the company, such as:

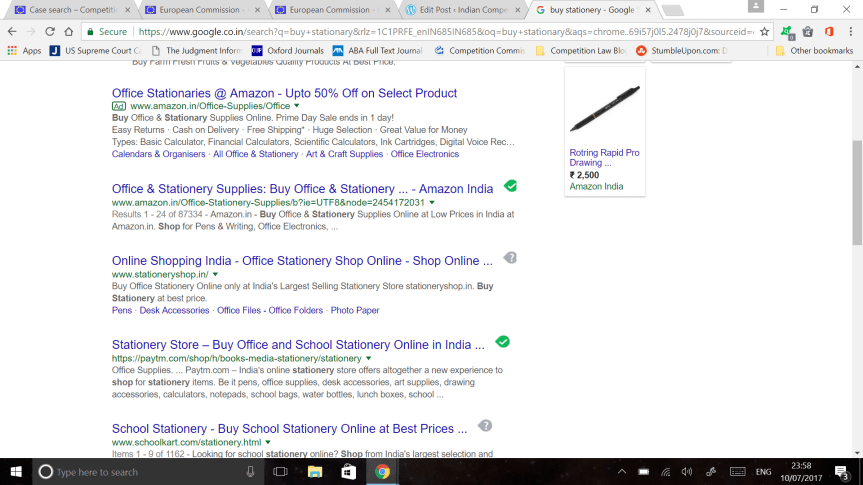

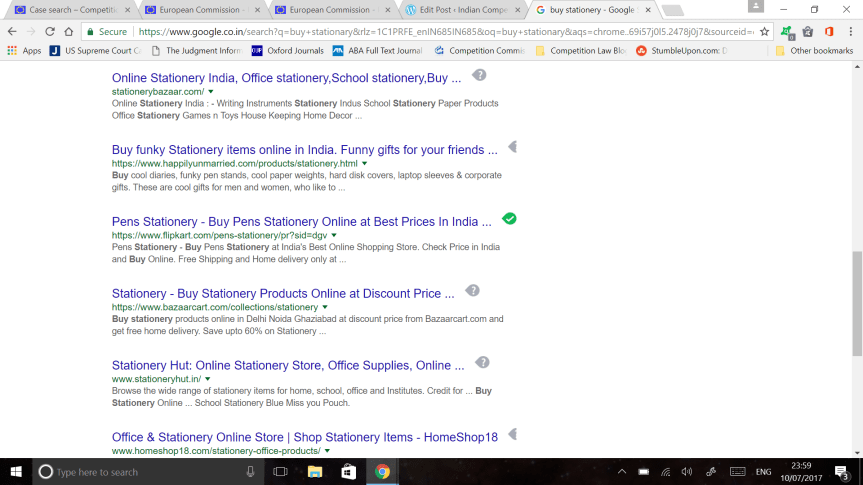

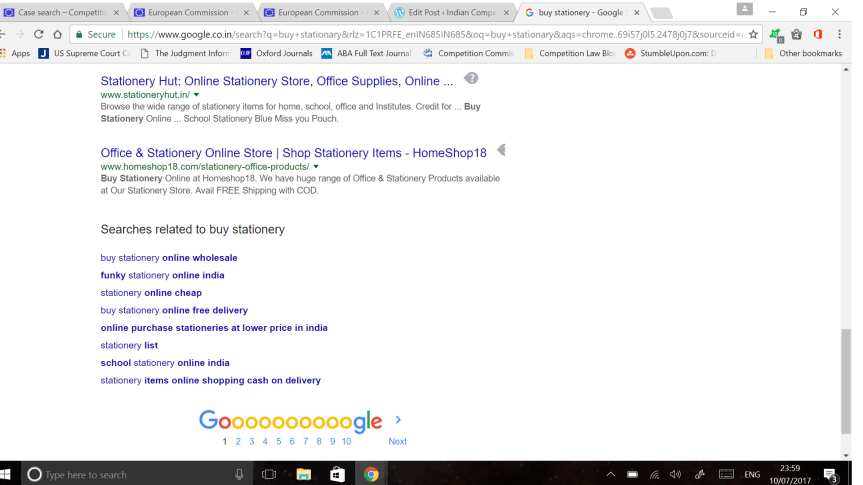

1. “…[i]n the first six months of 2015-16 (till September 2015), the D.G. noticed that while OP’s market share increased from marginally by 2% to 3%, Uber’s share increased at a faster rate i.e. by about 20%-22%.” [This is definitely due to a lower base rate.]

2. “It was further noted that from March 2015 onwards, Uber has maintained the second position. The D.G. also noted that from January to September 2015, Uber’s trip size registered growth of nearly 1200%, while OP’s growth has been about 63% during the same period.” [Same reason as above.]

3. “The D.G., thus, noted that backed by its marketing technology and logistics and financial support, Uber was able to successfully counter the pricing strategy of OP, and being able to sustain losses, which restrained OP from exercising market power in the relevant market. This was evident from the fact that similar strategy was followed by Uber and as a result, the gap in market share between OP and Uber narrowed down from 69% in January 2015 to 22% by September 2015.”

4. “Further, with the steady increase in Uber’s market share from 6 – 7% in January 2015 to 36-37% in September 2015, it could not be said whether OP would be in a position to hold on to its market share for a sustainable period for assessment of dominance in the relevant market.”

5. “Thus, D.G. opined that both OP and Uber have adopted ‘below-cost pricing strategy’. However, since the scheme of the Act only attracts the provisions of Section 4 when an incumbent is found to be dominant, the D.G. stated that OP can be said to have

indulged in abuse by way of predatory pricing, only if it is found to be dominant in the relevant market. Since OP was not found to be dominant, the D.G. concluded that OP did not contravene the provisions of Section 4 of the Act.” [Emphasis added]

6. “On the other hand, Uber, which entered the relevant market in 2013-14, expanded its network rapidly to account for nearly one third of the active fleet in the relevant market in 2015-16. In terms of annual number of trips, its share increased from 1 – 2% in 2013-14 to 30-31% in 2015-16.”

7. “…[U]ber, entered the relevant market in the year 2013 and garnered a sizeable market share in just about two years’ time. In terms of number of trips on monthly basis, its share increased from 0-1% in August 2013 to 36-37% in September 2015. Further, Uber showed a steady growth February 2015 onwards, with its share in terms of monthly number of trips having increased from 6-7 % in January 2015 to 36-37% by September 2015. Its entry as well as steady growth during the period of investigation shows that the market was evolving. While Uber’s entry, as the Informant has argued, did not dislodge OP during the period of investigation, OP’s declining market share post January 2015 reflects the competitive constraint posed by Uber and the fragility of leadership position in a dynamic business environment, as discussed earlier.”

8. “As a matter of record, in the present case, OP does not have an edge over all its competitors in terms of the size and resources. Interestingly, the investigation revealed that that Uber Inc., which is the parent company for Uber had a total capital investment of about 15 to 20 times of OP’s financial resources.” [The C.C.I. doesn’t seem to have made much of this, but it is important to note that “size and resources of the enterprise” and “economic power of the enterprise including commercial advantages over competitors” are two of the factors to be taken into consideration during an inquiry under Section 19(4)(b) and Section 19(4)(d) of the Act respectively.]

All this goes to show that Ola may owe Uber one for its victory, and also that Uber will be fully focused to ensure a favourable outcome in the Supreme Court to avoid the cross hairs of the D.G./C.C.I.